Ad Astra Per … STAR bonds?

A look at the problematic financing instrument behind the Chiefs stadium deal

By Percy Wegmann

Kansas was the first state in the nation to legislate STAR (Sales Tax and Revenue) bonds, and remains one of only three states with such a financial instrument. In their 27 year history, Kansas has issued $1 billion in STAR bonds. Now, the state wants to use them to finance up to $2.775 billion for a single project, a new Chiefs stadium. Why is this a bad idea, and what has history taught us about STAR bonds?

First, some basics

STAR bonds were established by the STAR bonds financing act (K.S.A. 12-17,160) in 1999. They are bonds issued by Kansas municipalities in order to fund private development projects. They create STAR bond districts that contain the development project (and others). Any sales tax collections from the district in excess of what was collected before the project (the baseline) go towards repaying the bond, but only for a limited period (between 20 to 30 years). After the bond has been paid off, or the bond period has ended, sales tax revenues flow to the state and municipalities as usual. The hope is that the increased long-term revenue from these projects and their knock-on effects will make up for lost sales tax revenue in the short term.

The STAR bonds financing act (K.S.A. 12-17,160) puts the Secretary of Commerce in charge of approving STAR bond projects. In the words of the Commerce Department, STAR bonds’ “intent is to increase regional and national visitation to Kansas while improving the quality of life across the state.”, with the hope that quality of life improvements attract and retain residents. The Department of Commerce enshrines the tourism requirement with two goals; 20% of the project’s visitors must come from outside of Kansas (national impact), and 30% must come from at least 100 miles away (regional impact).

STAR bonds are special obligation bonds, not general obligation bonds, so legally, neither the municipalities nor the State of Kansas are required to pay off the debt from their general funds, and the bond holders assume the risk of a project failing to generate sufficient sales tax revenue. Despite Schlitterbahn and Heartland Park closing before repaying their bonds, and Prairiefire being in default since late 2023, so far we have not seen the state or local governments cover STAR bond repayments using other revenue.

Do STAR bonds work and are they a good idea?

Whether you evaluate them on their own terms, or look at the bigger picture, the answer is no.

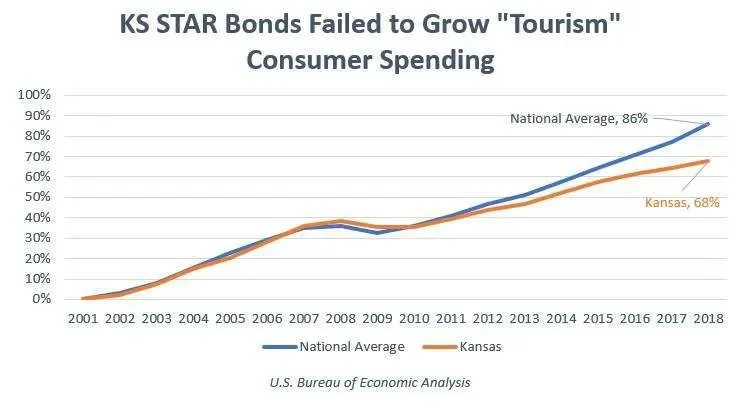

When it comes to promoting tourism, a KSLPA (Kansas Legislative Division of Post Audit) analysis from 2021 found that “only 3 of the 16 attractions we evaluated met Commerce’s tourism-related goals in 1 or both years we reviewed”. Even worse, as the Kansas Policy Institute reports, Kansas tourism spending has started declining relative to the rest of the US at the same time that we’ve expanded the STAR bonds program.

As reported by the Kansas Policy Institute

As for quality of life effects, a 2024 analysis from KSLPA found a mixed record at best. Their analysis confirmed what intuition would tell us, namely that people who left Kansas left primarily for employment opportunities, and people who chose to stay in Kansas stayed primarily to be close to family. Amenities did play a role, but not a determining one.

And what about the revenue goal? Well, KSLPA’s 2021 report included a break-even analysis for 3 of 16 projects which estimated that “it may be as late as 2132 before the state recoups the sales tax revenue it gave up for the 3 districts we evaluated”. Talk about having to wait for the long term!

STAR bonds seem to fail on their own terms, but even worse, they suffer from the same big picture problem as other development incentives like TIF districts. Government analysis of such programs ignores opportunity costs - what could have been done with this money if it remained in taxpayers’ hands? As a 2017 study from the Show Me Institute found about Kansas City, MO’s TIF districts, “the development seen in TIF areas is roughly what would have been expected in the absence of the TIF program”. So, municipalities forego revenue that could have been used to maintain public infrastructure like roads and water systems for … nothing.

The Prairiefire project has been in default on its STAR bond since late 2023. Recounting their interview with the developer of the Prairiefire Museum, KSLPA notes that

he said its cost exceeded the district’s projected rent revenue. He’d tried unsuccessfully to raise private funds before turning to STAR bonds. Doing so shifted much of the district’s costs to the state.

In other words, KSLPA learned what libertarians have known for a long time - the private sector is better at allocating investment than the government.

So what of the Chiefs? The reality is that Kansas City is a relatively small media market, and Kansas is a tiny state. Is that an attractive place for the Chiefs and the NFL to invest for the future, or could they make more money by moving the team elsewhere? There’s no reason to think that swaying their decision with public funds will be any less of a mistake than Prairiefire, but while Prairiefire was a $65 million mistake, the Chiefs will be more than a $2 billion one. When the bond holders come to the state begging, hat in hand, will legislators stand strong, or will they bail them out?

Olathe’s City Council and the Wyandotte County Commissioners have the opportunity to save all of Kansas from this mistake by rejecting the new STAR bond district. Let’s hope that they will.

Did you know

The Kansas Department of Commerce maintains a transparency database for STAR (Sales Tax and Revenue) bonds. For you data geeks out there, we’ve brought it into a Google Sheet where you can play with the numbers directly.